While Willy Chavarria has been working in the American fashion industry for quite some time, he has only recently begun to receive widespread recognition for his achievements. The designer, who established his own critically acclaimed label in 2015, won the Cooper Hewitt National Design Award for Fashion Design in 2022 and was a finalist for the CFDA American Menswear Designer of the Year in 2018. The Metropolitan Museum of Art included some of his garments in its 2022 exhibition titled In America: An Anthology of Fashion. Oh, and I forgot to tell you about his day job. He has held the position of senior vice president of design at PVH Corp.’s American fashion powerhouse Calvin Klein North America since 2021.

That Klein gig is undoubtedly due in large part to Chavarria’s ubiquitous influence. His hyper-voluminous, high-hiked trousers and his mixes of blue-collar workwear and formal tailoring have inspired similar styles in other designers. The oversized flower corsages from his spring show have made an appearance on red carpets, with some imitators even taking inspiration from his work.

Four days before his autumn/winter 2023 collection is set to debut in the closing hours of New York Fashion Week, we meet at Chavarria’s cosy studio in Brooklyn. I walk in as American Vogue’s editors leave and Chavarria, “a good friend and fit model,” is adjusting the hem of Erik “Chachi” Martinez’s ankle-length satin skirt. The skirt looks more like a priest’s soutane or something a mediaeval warrior might have worn than a skirt worn by a woman.

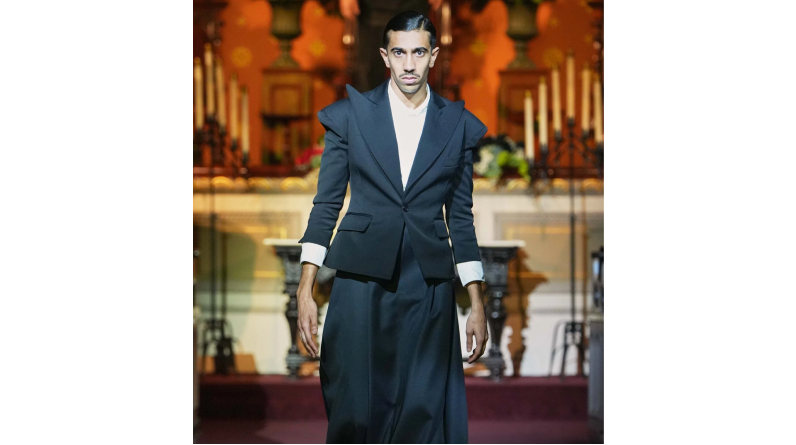

Chavarria, who is gay and who married his partner of more than 20 years, David Ramirez, in 2016, says, “When it comes to a queer identity in fashion, I do like that I do a masculine take to it.” Black, as with the majority of this collection, is strict and pure, relieved only by magnolia white. What Chavarria means by saying, “I pulled all the colour out,” is that he wanted there to be less visual clutter and more focus on the content. In other words, it won’t take attention away from the wearer. the outline, the finer points. Fresh start.

This person is very important to Chavarria. From the beginning, Chavarria and his casting director Brent Chua stood out for bringing an unconventional cast of mostly men of colour from the streets of New York and Los Angeles to his shows. “I’m always on the lookout for a very specific,’storied’ person,” Chavarria says. “It’s beautiful in a way that’s rarely seen on the runway, and it also has a strong emotional presence.”

When Chavarria presented his spring/summer 2023 collection at the Marble Collegiate Church on Fifth Avenue in September 2018, he showcased a wide range of ethnicities and cultures, a hallmark of his work. The Eagle, a gay bar popular with the 1970s leather crowd, was just one of the offbeat places where Chavarria had previously shown. Sharp tailoring in lustrous silks and mohair wools and grand gestures of rosettes and trains — the result, he says, of working with a specialist atelier — matched the opulence of the Fifth Avenue church’s interior.

There are many long coats in his newest collection, and there is something almost religious about the preponderance of black and Chavarria’s floor-length velvet or satin coats. Are we at a funeral or the opera, he deadpans.

Despite his playful demeanour, Chavarria is very serious about his work. Only about 30 stores around the world carry Chavarria, and the majority of sales come from the brand’s e-commerce platform, as he restricts wholesale to prevent deep markdowns at the end of each season. After the September show, there was a surge in custom orders from A-listers and other VIPs.

Chavarria says, “It was a big investment” to put on that show with its more expensive fabrics and elaborate designs. Success was ultimately achieved. A collaboration with Dickies, a workwear company founded in Texas, was showcased alongside the more luxurious offerings. There will still be “those lower-tier things” he says he will keep going. “I want to make sure they’re still a part of the brand identity because they’ve contributed so much to the success of the company,” the CEO said.

Obviously, Chavarria is not a young designer if he doesn’t sound like one. This is yet another peculiar facet of his life story. Currently, Chavarria is 56 years old. After twenty years of working for mass market labels like Joe Boxer and American Eagle Outfitters, he launched his own label.

Also Read :Southend townhouse offers peaceful beach town living with easy access

The Met exhibit of Chavarria’s ensemble features enormous wool trousers with silk-taffeta boxer shorts peeking out from underneath—an odd relic of the era. They’ve got his first name printed in large, bold letters across the top of the groyne, right where a name like ‘Calvin Klein’ would normally go.

Chavarria was born to an Irish American mother and a Mexican American father in Fresno, California, a city with a large population of migrant farm workers. He claims that “the look” of people rather than their clothing was the primary source of inspiration for him. He was always interested in the clothes regular people wore as a kid. In his early twenties, he uprooted to San Francisco to pursue a degree in graphic design, and more importantly, he started getting out and observing how other people put together their outfits, as well as beginning to dress up himself.

At Ralph Lauren’s urging, Chavarria relocated to New York in 1999 to launch the company’s cycling line, RLX. The five years he spent there “probably where I got most of my education,” he says. It’s all in the details—the design, the quality, the skilled execution. In October of 2010, he opened his own multi-brand menswear store, Palmer Trading Company, in New York’s SoHo neighbourhood. He worked at American Eagle as design director until 2012. The store sold a variety of new and vintage Americana products.

Chavarria’s decision to launch his own brand was inspired by a suggestion from a Japanese retailer. In retrospect, he laughs and says, “Everything was really oversized” because he was his first fit model. The store’s closures increased as the company expanded, ostensibly for publicity purposes. Adding, “And the rent was like $30,000 a month,” Chavarria grimaces. The store eventually shut down, but Chavarria took his business to Brooklyn, where it flourished.

After putting Chachi in a simple ribbon-cotton tank top, Chavarria adds a luxurious silk chiffon shirt on top. Chavarria’s clothes have always felt grounded in reality, with an emphasis on wearability even in his more experimental designs. This could be because he chose not to pursue a traditional fashion education. He says, “I missed out on the wild side of college fashion.” In the context of business, of course. Perhaps this has turned out for the best.

Chavarria considers his style to be a form of political protest. A month into the Trump administration, his first 2017 presentation featured black and brown models literally caged, while his second featured men dressed provocatively for a gay cruising event. His clothing defies conventional notions of masculinity.

If you’re not pushing the envelope of style, in his opinion, you’re just making clothes. So, yes, I do purposefully weave in a lot of narrative elements, as well as political and social justice themes. It’s possible for me to make money tailoring garments, but only if my work improves the lives of people everywhere.